Attention Houston-based readers of Quarter Mile Smile. You are in for a real treat. Professor Philip Bess from the University of Notre Dame School of Architecture will be in Houston to give a lecture at the University of Saint Thomas at 7:00pm this Thursday, April 23rd. You may recognize his name from a few articles posted in the Quarter Mile Smile Reading Room. Of note, he authored a very good two-part article in Public Discourse that makes an excellent case for urbanism and discloses some of the issues with sprawl. If you can find time in your schedule to attend this lecture, you will enjoy it. It is free and open to the public.

Placemaking

All You Need is Love: Why Love is the Secret Ingredient in Marinara and Place Making – Part 2

If men loved Pimlico as mothers love children, arbitrarily, because it is theirs, Pimlico in a year or two might be fairer than Florence. – G.K. Chesterton

In my previous post, I spoke about how the prerequisite for creating any place worth dwelling in is love. I suggested that money without love will lead at the very least to mediocrity and at the worse to design atrocities that are often a violation of the spirit of a place and the people who live there.

South Bend, Indiana, is Pimlico

You have to love to see. When I arrived in South Bend, Indiana, in 2009, its citizens were the worst detractors of the place. The downtown had yet to shake a reputation it had earned a couple of decades prior for being a crime-ridden, unsafe place with little to do. A once glorious downtown had, through terrible urban planning mistakes, been reduced to pawn shops and low-end bars that emptied drunks onto the streets nightly.

And yet, a dedicated group had started loving the downtown years before I arrived, and happily, the city had put resources and money behind them. When I arrived, the old reputation was simply a bad myth waiting to be dispelled. Gone were the pawn shops, the wig shops, and the drunk bars. There were retail shops, restaurants, a pleasant streetscape with newly installed benches and flower beds. Many building facades had been restored through a very successful grant program. There were several popular festivals that brought thousands into the downtown regularly. But South Bend’s transformation was still in its early stages. Many storefronts were still vacant, many facades still needed rehabilitation, and the mega-mall in the next municipality, the one with all the stores that used to be in downtown South Bend, still proved to be a more powerful pull than the collection of stores the downtown had to offer.

Before long, I found myself falling in love with little South Bend, a place that had seen better days. And because I loved her, I could see the city’s potential, the better days ahead. And this seeing inspired my actions. When I walked down the street, the empty storefronts were not merely “empty,” they were an unrealized possibility. It was as though the empty shops were calling out to me to fill them the way a child calls out to a mother to fill her empty stomach.

I was not alone. The as-yet unrealized possibility of South Bend called out to a dedicated core of volunteers, business owners, and city employees. South Bend is turning itself around because people began to love her and continue to love her in spite of her unrealized potential. The historic and once abandoned State Theater in downtown South Bend has become home to a wonderful little brewery, a monthly market, and a series of interesting performances because people loved her and saw the potential. Downtown South Bend is abuzz with people every first Friday of the month because people joined together to create a fun monthly event that has grown in popularity since its bumpy inception. New residences are being built, the empty shops are filling up, and historic buildings are finally being rehabbed. The one-way streets that once directed traffic around the city like a raceway are finally being converted into two-way streets again, all because people loved South Bend and did not “move to Chelsea” — or in South Bend’s case, to the nearby town of Granger. In fact, people are finally moving to South Bend, not merely moving away or visiting during an occasional Notre Dame football game.

Note: South Bend is celebrating 150 years in 2015. The community has banded together to create a year-long slate of activities, celebrations, and projects. The concentration of activity will occur on the anniversary weekend, May 22nd. Find out more at: http://www.sb150.com/.

South Bend Brew Works at the State Theater. This local establishment began as a pop-up home brew supply company and was transformed by the sheer will and passion of its owner and a group of committed supporters. This does not happen without love.

Galena Park in Texas is also Pimilco

I was recently in Galena Park, Texas, for a meeting. Now Galena Park is not the prime example that would come to mind when the subject is walkability. Galena Park is a small industrial city of just over 10,000 people located on the north bank of the Houston Ship Channel, a highly industrial area given over mostly to rusty ocean-going ships and the facilities to load and unload them. The most common way to enter Galena Park is via Clinton Avenue, a road which the industry in the area backs up onto as if it were a wide alley and not the main thoroughfare though the city. There is little landscape or streetscape to speak of, and the street must be constantly swept to keep it free of the debris common to any area that sees as much truck traffic as Galena Park. There are no restaurants of note in Galena Park — certainly no little gem just on the verge of being discovered by Houston foodies—no cute little clusters of shops or a neighborhood full of pristine expertly preserved historic period homes. And yet I would argue that Galena Park is not only loveable, but loved. And that because she is loved, she is changing.

After my arrival, I stood on the front lawn of Galena Park’s city government building in front of a metal torch mounted on a brick pedestal in the center of the lawn. The torch, a gift from the local American Legion over 50 years ago, used to house an “eternal flame” at its top, which long ago burned out and was never repaired, resulting in a very dead “eternal” flame. With the group that had assembled on the lawn to contemplate the location and design of a new monument to serve as a gateway to the city was a gentleman from the public works department. He spoke of the American Legion with pride. He pointed to a small out-of-the-way historic marker and began to share the history of the city and the important role its citizens had played leading up to the Battle of San Jacinto, those famous 18 minutes during which Texas was born with the defeat of General Santa Anna. This public works official became excited about the idea of incorporating the historic marker into the area by the new monument. Others spoke of incorporating benches by the monument for the frequent visit by the city’s senior citizens, and of wider beautification efforts planned along Clinton Drive which included fencing for industry and an ambitious landscaping plan. The group shared aspirations for a new city hall that would be worthy of the monument they were planning.

Galena Park is loved, of this I have no doubt. How many places can you think of where a town’s retired citizens show up at city hall just to visit, not because they need something, but because they like to go to city hall? We can say about Galena Park what G. K. Chesteron said about Pimlico: that, “If men loved Galena Park as mothers love children, arbitrarily, because it is theirs, Galena Park in a year or two might be fairer than Florence.” People right now, this moment, are loving Galena Park into beauty. I have no doubt, given what I know of the people I met there that, given half a chance, they will succeed. Unless, of course, someone who doesn’t love the place, who only wants to use it as a means to some other end, comes in and overrules them in a manner akin to a government bureaucrat taking possession of your child on the pretense that he or she knows better than you do how to plan for their future.

Photo Credit for top of post: Peter Ringenberg, South Bend, IN.

Lessons from Rome 1: Every Man’s House Is His Palazzo

The Evolution of the Palazzo

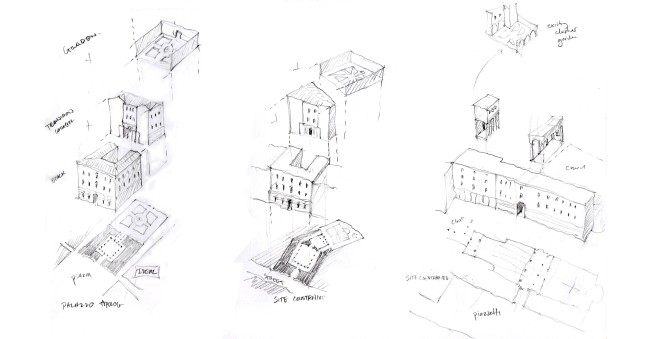

As Roman houses developed through the medieval period, added elements of fortification, such as towers and gated doors, served a practical purpose in a city that was often besieged.

A Mix of Uses in the Renaissance Palazzo

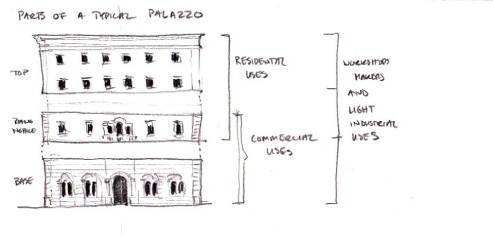

The basic form of the renaissance palazzo has three parts. The base of the building, containing a large door and courtyard, was a place for business and for secure storage. Above this, an elevated and enlarged floor, called the piano nobile, held the important public spaces of the noble family. The floors above the piano nobile, the top of the building, could be subsidiary family space or room for tenants, and staff.

A single palazzo building could therefore contain commercial, residential, and industrial spaces, all united by the patronage of the noble landlord. Rather than keeping different activities and uses in different buildings, the Palazzo keeps them all together, separated by floor, room, or hall.

Infinite Flexibility is Sustainable and Helps Build Community

As an urban building type, the palazzo form has the advantage of infinite flexibility. Because a palazzo is not designed for any one purpose, many different uses may come and go in the same building over the course of its history, provided the basic construction is of durable materials.

The diversity of residential space adds another kind of flexibility. Romans of different social and economic status live and work in the same building today, as they always have. A rich public life is possible because of this diversity. All classes of citizen are represented in the neighborhood markets, festivals, and daily routines.

The Magic of the Six Story Building

There is also an apparent limitation in the palazzo form which actually has had an advantageous effect on Roman urban life. Load bearing masonry construction limited the height of the renaissance palazzo to about six stories. This limitation to the number of upper residential floors provides neighborhoods with a population density high enough to support commerce, but low enough that a resident can know their neighbors. It supports the kind of relationships necessary for civic life. In short, it makes it possible to know one’s neighbors. This height limitation also means that an elevator is also not an absolute necessity, and a comfortable walk up a stair, like a comfortable walk down a street, is good for the citizen.

Let’s Make an Urban Fabric Pizza: Functional vs. Form Based Zoning

You’ve met them, those “food separatists” that cannot stand for one item on their dinner plate to touch another. A random pea rolling into the mashed potatoes is greeted with a look of distain, and gravy or any sort of escaped sauce that made its way off the meat might be the cause of apoplexy. Likely one of them was the inventor of the divided plate of the sort one sometimes sees in school cafeterias. A plate that keeps order, and peas in their proper place.

There are others that take relish in the unplanned and accidental combination of flavors that may take place during the course of a meal; who even actively engage in food combining, dropping leaves of their salad into their spaghetti and swirling peas into their mashed potatoes just to see what flavors might result. Regardless of whether you are a food separatist, a food combiner, or stand neutral on the subject, all will likely come to complete agreement in the case of a pizza. Who in their right mind, or even addled mind, would ask for a deconstructed pizza?

Photo Credit: http://travelingdictionary.com

Pizza is defined by its particular combination of crust, sauce, cheese, and toppings. Even the pizzas of experimental cuisine adhere to this basic structure even if they swap out tomato sauce for pesto or mozzarella for goat cheese. If the crust were naked, the sauce, and meats or veggies were in a separate bowl, and the cheese melted on a separate plate, we would not find ourselves tempted to eat it. Or at the very least, we wouldn’t call it a pizza.

Pizza as Metaphor

It is for this reason, precisely because of the necessary mixing and combining that goes into a pizza, that famed architect and urban planner Leon Krier (often credited as the intellectual god father of the New Urbanist movement) has elevated the pizza from mere restaurant item to the official food mascot of New Urbanism. Krier makes use of the pizza to argue against use-based zoning.

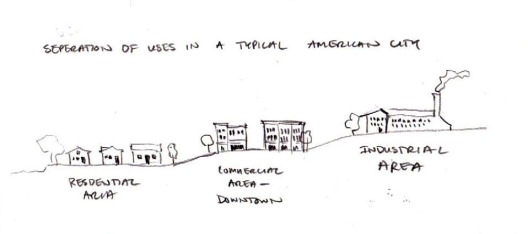

While we see a deconstructed pizza as ridiculous and unappetizing, we have gone to great lengths to create deconstructed places. Before the advent of the car, towns and cities were created in such a way that the majority of daily needs could be met on foot. Work, groceries, clothing, schools, libraries, doctor’s offices, parks, playgrounds, and retail establishments were all within a 10 minute walk or within an easy street car ride. Large format, single family homes were down the road from duplexes and apartments.

Then along came use-based zoning. No longer could a corner store or neighborhood pub occupy the end of a residential block. Retail establishments needed to be grouped with other retail establishments. Office buildings and places of work were separated with other office buildings and places of work, so on and so forth. This grand sorting out of places by function was only made possible by the car. And while many people do have cars, this type of planning removed the choice and made having a car a necessity for many.

The Degradation of the Pedestrian Realm

The result on the visual quality of the pedestrian realm was not neutral. As the necessities of life became unreachable by foot, there was then no need to create retail and commercial buildings that had sidewalk appeal designed to draw in pedestrians to their place of business. So the loss of a multitude of functions within a walkable sphere also led to the degradation of the pedestrian realm itself. (See my Speed of Christmas post).

Zoning Based on use vs Zoning Based on Form

Often those who promote the creation of walkable places promote form-based code as a preferable alternative to use-based zoning. The proponents of walkability understand, just as the promoters of use-based zoning, that it does not work to have a big box store with a vast expanse of asphalt parking lot located next to a single-family home. But instead of prescribing against retail stores next to homes, form based codes prescribe the size that a building can be. They limit things like the height, width, length, and set-back and leave the use up to the owner. Since a Walmart cannot fit inside the equivalent of a three story brownstone, the effect is that Walmarts are not located next to houses, whereas, a small store or coffee shop could be.

Walkable Places are More Attractive Places. More Attractive Places Increase Property Values

By allowing a mixture of uses to flourish within a neighborhood, walkability becomes possible again as people have places to walk to. As people begin walking to places, businesses will take more care with their exteriors. And as a street becomes more attractive, it is not just the pedestrians that benefit. Andrew Burlson, a real estate developer and consultant with The Fourth Environment shows how in his presentation on the Net Attraction Framework that as a place becomes more attractive, it increases the property values for buildings and homes located adjacent to those attractive places.

Walkable Places Help Reduce Traffic and Infrastructure Costs

When every errand does not require a car, traffic volume decreases. Thus every car trip that is replaced by a pedestrian trip makes life more pleasant for those who still need to travel a greater distance by car. It also reduces the wear and tear on the roads. You would think by how enthusiastically we lay new roads and widen highways that they must be cheap to build and maintain, that perhaps cities and counties are getting a volume discount on the materials. But the truth is, roads are expensive. Expensive to lay and expensive to maintain. Thus creating more walkable places not only alleviates stress on traffic during peak times, but also decreases the burden on our roads.

So, let’s advocate for pizza and everyone can benefit, even those who prefer spaghetti!

Further Reading

Much has been written on the logic of form-based zoning and the repercussions of use-based zoning. See:

The Power of a Pilot

Rhyme and Meter Project in front of the Albuquerque public library in 1999. This project launched during poetry month.

Several years ago, while living in Albuquerque New Mexico, I conceived of a pun-inspired public art project. The project, entitled Rhyme and Meter, brought poetry and art together in the public realm. Excerpts of poems were affixed to downtown parking meters which were then painted by local artists as an illustration of the poem. In essence the parking meter became the page in a public book of poetry.

When I first started sharing the idea, it was hard for people to imagine. After all, they had never seen a parking meter covered with art and a poem. People liked the idea of transforming a disliked but-necessary part of the downtown parking infrastructure into a vehicle for beauty, but some people assumed that I would be executing the project as a clandestine effort conducted under the cover of night and not as a project fully blessed by the city’s mayor and head of parking.

They were wrong. But they were only wrong because I inadvertently stumbled across the power of the word “pilot” program, a term whose power I would later hear Andres Duany, the founder of the Congress of New Urbanism, espouse to a room full of urban visionaries.

The organization that made the Rhyme and Meter project possible and to whom I owe this happy discovery was the Downtown Action Team. They embraced the concept of adorning the downtown parking meters with poetry and art as part of a larger downtown revitalization effort. They not only allowed me to pursue the project under the umbrella of their organization, but also provided invaluable guidance. It was one of their members that suggested I scale back my initial vision of a 20 parking meter project to a four parking meter project and call it a “pilot.”

It would be much easier to get permission to paint four parking meters, they explained, than 20. The project would seem less threatening and thus less risky for city officials to support. If the meters turned out terrible, then they could easily be repainted. Since there was a strong potential for positive publicity and no cost for the city in undertaking the “pilot program,” permission was relatively easy to secure. Much to the surprise of many of my friends, the project was approved with little effort by the head of parking and the mayor’s office, despite a lack of strong buy-in.

While that stronger buy-in would be necessary for the larger project, which was to involve several blocks of painted poetic parking meters, only weak buy in was needed for the pilot project. The pilot would serve as a proof of the concept, inspiring others to get on board for the larger project. Four parking meters also required fewer resources in terms of paint, plaques, and the number of artists required. Since fewer resources were needed, this also meant I needed to convince fewer sponsors about the merit of the idea. We were also able to use to pilot as a way of experimenting with materials. We tested sign paint on one meter and auto paint on another. We tried a metal plaque for the poetry on one of the first four meters and painted the poem directly on another.

So in summary, pilots:

- Make it easier to secure buy in

- Typically require fewer resources

- Allow for course correction

- Help stakeholders visualize new ideas

While the famous architect and planner Daniel Burhan is often quoted as having said “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood,” there is also a problem when we develop creative, innovative projects that are never realized. Sometimes men are not willing to have their blood stirred, and at those times a pilot may be just the mechanism needed to make the vision immediate and clear.

I understand that not all projects will lend themselves to being piloted/ But since my discovery of the pilot, I have employed it time and again.

In the end, we launched our pilot with a media event that featured an unveiling and “meter reading.” Tim Durant, the ombudsman for the mayor at the time slipped down to the project site, took one look at all the members of the media present, the positive reception by the attendees, and promptly phoned the mayor to come on over. In an on-camera interview, the mayor said “Yes, we are planning on doing all of downtown.” I nearly fainted. My initial vision had only been for 20 meters. Thus sometimes a pilot can make your project bigger than you had initially planned. Over the next two years we rolled out two more projects bringing the total number of meters we completed to 25. No, I did not get to all the meters in downtown before I needed to move back to Texas for family reasons. But the power of a pilot made progress a possibility.

Transforming Empty Storefronts 1: Pop-up Shops

By Tamara Nicholl-Smith

When I began my work with Downtown South Bend, Inc. (DTSB) in the summer of 2010, there were five empty storefronts on the primary retail block in the downtown. The Holiday Pop-up Shop Program was the remedy we cultivated in cooperation with the redevelopment commission, private landowners, the real estate community, existing shop and restaurant owners, and a small band of volunteers.

Downtown South Bend main retail block in 2010.

Program Overview

The program offered start-up and established retailers no-cost short-term leases (November – December) in a downtown South Bend storefront through a juried selection process. Businesses were selected based on the following criteria:

- The appeal of their product mix to holiday shoppers,

- How well their concept worked in synergy with established full-time tenants,

- Their ability to add excitement to the festive holiday atmosphere through in-store events, promotions, and

- The quality of their proposed window displays.

DTSB promoted the locations and hours of the pop-up shops in conjunction with advertising and marketing of downtown holiday events and activities.

Program Goals

- To provide the retail density necessary to support current downtown retailers/restaurants.

- To build upon the success of existing downtown holiday activities.

- To leverage the opportunity and good will presented by the program to develop long-term lease prospects for the spaces.

- To shift the downtown retail narrative in the media and populace.

- Create hope in the midst of a recession through a successful short-term wins.

Additional Benefits

Through the juried application process the Pop-Up Shop Program gave DTSB a say in the downtown business mix, a decision usually left only to the real estate agents representing the building owners. This allowed DTSB to work from a cohesive overarching vision.

By lowering the barriers to entry to a brick and mortar storefront, local entrepreneurs had a way to test their ideas in the market place and determine if shop ownership was truly a fit for their lives.

Toolkit

Below are the documents we created to run the program. You are free to download them and use them as the basis for your own community’s initiative. There is only one catch, you must acknowledge the City of South Bend, and Downtown South Bend, Inc. as the source of inspiration for your project. That’s it. Otherwise, they are free!

- International Downtown Association Presentation:”Three Years of Holiday Pop-ups in Downtown South Bend – How We Did it & How You Can (Pop-up for the Holidays_IDA2012_FINAL)

- Prior Media: SelectedPressfrom2010Program

- Example Proposal: HolidayRetailProgram_2011Proposal

- Landlord FAQ: 2012_HolidayShop_FAQ for Building Owners

- Landlord Interest Sheet: Building Owner Interest Sheet_2012

- Applicant FAQ: 2012_HolidayPop-upShop_FAQ

- Participant Application: 2012_DTSBHolidayPop-Up_Application

- Participant Move-in FAQ: 2011_Holiday_Pop-Up_Move-in_FAQ

- Participant Agreement: 2012 Program Agreement Information

- Legal documents: Holiday Pop-Up_Lease_2012

Results:

Several of the pop-up shops remained and became permanent downtown businesses. Others, inspired by their positive experience returned at a later date, once an appropriate space was located.

Results by Year

- In 2010, one out of the four pop-up shops signed a lease and remained.

- In 2011, one of out the four pop-up shops, inspired by their success signed a lease and opened that spring.

- In 2012 three out of eight pop-up shops signed a lease and remained. An additional fourth shop found a permanent downtown location the following year.

In 2010, this empty storefront was transformed by Pop-Up Shop participants into a toy store and arts collective called Imagine That!

Considerations

The rapid turn-round and intense amount of energy required to participate in the pop-up shop program seemed to favor the co-op model of business where many individuals, all with a stake in the game were involved. However, the permanent storefront seems to benefit from the single-owner model.

Final Thoughts

Solutions are contextual. The pop-up shop program was created out of a set of circumstances brought about by the recession. The program proved to be a necessary intervention when the usual tactics yielded no results.

We always considered the program a temporary measure. One day, we hoped, the country would no longer be embroiled in a recession. Real estate prices would rebound, retail sales would recover, families would stabilize in homes, and downtown would once again be a vibrant center of retail, restaurants, and cultural activities.

Indeed after four very successful years (2010-2013), the program in Downtown South-Bend is being discontinued in favor of a year-long business incubation program currently in development. Meanwhile, downtown South Bend is stronger than it was before the recession because of the number of people engaged in its successes, specifically the number of people who are NOT employees of Downtown South Bend, Inc. or the City of South Bend who stake some claim of ownership in the downtown, and who each day, through their own personal connections are ambassadors and defenders of a vibrant downtown community.

Perhaps most importantly, the program brought hope.

Photos from 2010 and 2011 pop-up shop grand openings.

Media Articles

- From 2010 Program: DTSB Offers Stores for Free, Tenants Selected, Shop Owners Test Waters, Program Exceeds Expectations, Pop-Up Proves Successful

- From 2011 Program: Consumers Offer Ideas for Pop-Up Program, Pop-up Program Asking for Applicants, Local Stores See Boost in Sales,

- From 2012 Program: Bicycle Gallery Becomes Permanent, Three Pop-Up Shops to Stay in Downtown, Pop-Up Shops Start to Take Shape, Pop-Up Shops Open

Other Pop-up Shop Programs

View the links below to see how other places have implemented their pop-up shop programs. Each was designed to address different challenges within distinctly different contexts.

- Downtown Promotion Reporter: Pop-Ups Made Downtown More Festive

- Denver: Pop-up Republic

- Downtown Pittsburgh: Project Pop-Up

Contact Tamara Nicholl-Smith through LinkedIn.

Note: Posts of this sort are intended to serve as a toolkit for those in the field. This post will be permanently linked from the Theory in Action page. If you know of other programs like this not mentioned in this post, please share them in a comment.

Welcome to Quarter Mile Smile

by Tamara Nicholl-Smith

Every morning, Monday thru Friday, I walk out my front door, descend the stairs to the parking garage beneath my Houston condo complex, and use my automatic clicker to unlock my black Hyundai Elantra with black leather interior and blue-lit dials. After an old fashioned turn of the key in the ignition, I emerge from below onto the street as if emerging out of the bat cave. From there it is a short drive to one of Houston’s many major highways.

When I maneuver my modest little car from the on-ramp onto nearby Highway 288, I am no longer merely a commuter; rather, I am transformed instantly into a competitor with thousands of others in a massive video game being played with very serious stakes. The aim of the game, in my case, is to make it the 20.8 miles from my home to my office in the Houston Ship Channel Region alive, and if all goes well, relatively undamaged, except for some seriously frayed nerves.

The obstacles and dangers are many. Cars wiz by like enemy missiles.. Erratic vehicles weave in and out of lanes; drivers repeatedly insist on traveling in my blind spot; trucks kick up rocks and other projectile objects and aims them at my windshield; and a on a regular basis vehicles of all sizes attempt to merge into my exact place on the road. My controls in this great video game are my steering wheel, accelerator pedal, break, and horn.

Along the way, I am reminded by a series of Texas Department of Transportation LED billboards, of how many have lost this game this year and given their lives over to the Texas freeways. It seems as though I am late at least one day every week because of a major wreck blocking one or more lanes of traffic. My first instinct is to be grumpy; my second is to realize that the wreck involved someone’s wife, husband, grandfather, grandmother, child, or best friend, a person that may now be gone to us forever.

And I then think, is it worth it? The daily freeway commute is a game of odds. It is not a matter of if someone will be hurt, but when, and what are the odds it will be me? I make the trek for now because I believe I am well placed in my current position. But I question whether I am not a bit touched in the head. I live within five miles of hundreds of jobs for which I am qualified, but I choose to join so many of my fellow Houstonians in the great, dangerous “freeway commuter game” each day.

Libertarians of a certain stripe extol the virtues of an auto-centric transportation infrastructure, declaring: “We Texans love our cars. We want to travel where we want to travel when we want to travel. We do not want to be beholden to a schedule.” I am not one to argue that we do away with freeways, roads, or even cars. But I will argue for options: options which can only come to us through changes both in individual behavior and in the way we build our cities and plan our infrastructure.

The freedom being extolled is a bit of an illusion anyway, given that there are certain times of the day when you can’t really get anywhere very quickly — not even ten yards in ten minutes. And as 5,000 people a month move to the greater Houston area, the reality behind the illusion is becoming clearer to anyone paying attention. How free is one’s movement when a trip that used to only take 10 minutes now takes 30? How many people, when given the option, would choose to spend one to two hours of their day in their car traveling to and from work (even bolstered by the very best of audio books) instead of spending that time relating to their family and friends, or volunteering in their communities for causes they deeply believe in? Very few, I would imagine.

And how truly unbound by schedule are commuters anyway? There is a reason for rush hour. Our schedules may not be set by a train or bus time table, but it often is set by our respective employers who command a schedule that drags us from our beds and out into the video game at a particular time each day. We each make a rational decision to go to and from work each day, but the sum total of all those “rational” decisions is an utterly irrational result: gridlock. None of us can get home for hours.

I am not one to rant without solutions, but I am also not so naïve as to imagine that at any time in the near future my city, famous for and proud of its spaghetti-like tangle of freeways and miles of low-density housing, is likely to transform itself into one noted for its high-quality, ever-present public transit system.

But what of those who would not choose the status quo? What of those who cannot drive at due to physical or financial inability? Should those citizens not be presented with another option? Do they not “rate” as people who also should have freedom, the same sort of freedom libertarians in their cars claim for themselves, all the while expecting everyone else to pay public money for wider highways to support that “right”?

Philip Bess, a professor of urban design a the Notre Dame School of Architecture argues in one of the essays I link to on this blog that we should consider it an obligation to provide as an option walkable, mixed-use, socio-economically diverse neighborhoods within which the majority of daily activities can be reached within a ten minute walk. Combine building patterns of this sort with the sort of well-placed transit options espoused by supporters of transit-oriented development, and we will have gone a long way to relieving pressure on our auto and truck-centric infrastructure and have moved to a more socially just distribution of options.

What of the behavior side? Those who study these matters say that a substantial portion of the congestion on the roads during rush hour consists of people running errands that have nothing to do with commuting to work or school. Perhaps a simple shift of the timing of errand-running might help, but the structural solution of providing for those needs in close proximity to residences would also be beneficial.

Technology should also have made possible many more options than we currently seem to be taking advantage of. With laptops, the internet, an easy access to video chat programs such as Skype, Face Time, and Google hangouts, it seems as though there should be less demand for people to be physically present every day of the working week at their offices. Granted, not all jobs can be done remotely. A cashier cannot “dial-in” to his or her job, nor can a stocker in a grocery store, a security guard, or a chef in a restaurant. Working remotely is mainly possible for office workers like me. Perhaps allowing just a day or two a week working from home would relieve stress on the roads (and in workers) without costing any productivity.

How many corporations with multiple locations have employees that live near one location, but whose job requires them to report to a much further location? How much of this movement is strictly necessary? How many companies could provide drop-in spots for employees to work a day or two a week from a location closer to their homes?

If Houston, and places like it, are to avoid the fate of Los Angeles, or even worse, Mexico City, it will be necessary to:

- Change the way we build our cities;

- Incorporate alternative modes of travel into our infrastructure (transit, cycling, walking);

- Come up with ways to motivate changes to our behavior and the way our work week is structured.

Essays and articles on this blog are meant to suggest ways in which we might begin to implement ideas to meet these goals. Future posts will link to or discuss solutions from the perspective of policy, design, behavior change, and high and low-tech innovation. While this project is a work in progress, already on this site you will find a wealth of resources:

- The Fellow Travelers page provides a listing of groups that have done serious hiking, research and projects related to creating quality places.

- The Reading Room links to articles and books that provide solid theoretical foundation, as well as examples and inspiration.

- If you need a practitioner, check out the Really Good Architects

We will be building out the content on all these pages, so check back often.

The inspiration for this blog is two-fold:

- To solve problems that arise from the way we currently build and get around in our cities;

- To create places that delight, nourish, and provide the context for us to be happy

Thus: The Quarter Mile (five minute walk) Smile!